Files and Directories

The part of the operating system responsible for managing files and directories is called the file system.

It organizes our data into files,

which hold information,

and directories (also called "folders", for example, on Windows systems),

which hold files or other directories.

The shell has a notion of where you currently are, and as we'll see, works by running programs at that location. For this reason, the most fundamental skills to using the shell are navigating and browsing the file system, so let's take a look at some important commands that let us do these things.

To start exploring them, let's open a shell window:

$

The dollar sign is a prompt,

which represents our input interface to the shell.

It shows us that the shell is waiting for input;

your shell may show something more elaborate.

Working out who we are and where we are

Type the command

whoami,

then press the Enter key (sometimes called Return) to send the command to the shell.

The command's output is the identity of the current user,

i.e., it shows us who the shell thinks we are (yours will be something different!):whoami

nelle

So what's happening? When we type

whoami the shell:- Finds a program called

whoami - Runs that program

- Displays that program's output (if there is any), then

- Displays a new prompt to tell us that it's ready for more commands

Next, let's find out where we are in our file system by running a command called

pwd

(which stands for "print working directory").

At any moment,

our current working directory

is our current default directory.

This is the directory that the computer assumes we want to run commands in

unless we explicitly specify something else.

Here,

the computer's response is /Users/nelle,

which is Nelle's home directory:pwd

/Users/nelle

Home directory

The home directory path will look different on different operating systems.

On Linux it will look like

/home/nelle,

on Git Bash on Windows it will look something like /c/Users/nelle,

and on Windows itself it will be similar to C:\Users\nelle.

Note that it may also look slightly different for different versions of

Windows.Alphabet Soup

If the command to find out who we are is

whoami, the command to find

out where we are ought to be called whereami, so why is it pwd

instead? The usual answer is that in the early 1970s, when Unix - where the Bash shell originates - was

first being developed, every keystroke counted: the devices of the day

were slow, and backspacing on a teletype was so painful that cutting the

number of keystrokes in order to cut the number of typing mistakes was

actually a win for usability. The reality is that commands were added to

Unix one by one, without any master plan, by people who were immersed in

its jargon. The result is as inconsistent as the roolz uv Inglish

speling, but we're stuck with it now.Real typing timesavers

Save yourself some unnecessary keypresses!

Using the up and down arrow keys allow you to cycle through your previous

commands - plus, useful if you forget exactly what you typed earlier!

We can also move to the beginning of a line in the shell by typing

^A

(which means Control-A) and to the end using ^E. Much quicker on long

lines than just using the left/right arrow keys.How file systems are organised

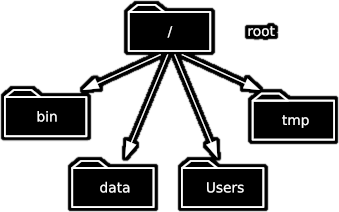

To understand what a "home directory" is,

let's have a look at how the file system as a whole is organized.

At the top is the root directory

that holds everything else.

We refer to it using a slash character

/ on its own;

this is the leading slash in /Users/nelle.Let's continue looking at Nelle's hypothetical file system as an example. Inside the

/ directory are several other directories, for example:

So here we have the following directories:

bin(which is where some built-in programs are stored),data(for miscellaneous data files),Users(where users' personal directories are located),tmp(for temporary files that don't need to be stored long-term),

We know that our current working directory

/Users/nelle is stored inside /Users

because /Users is the first part of its name.

Similarly,

we know that /Users is stored inside the root directory /

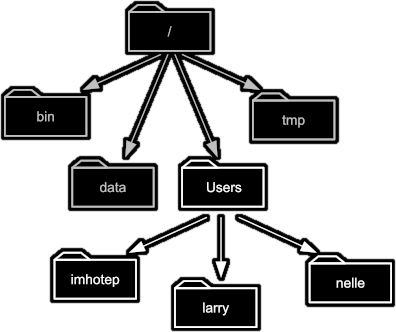

because its name begins with /.Underneath

/Users,

we find one directory for each user with an account on this machine, e.g.:

/Users/imhotep,

/Users/larry,

and ours in /Users/nelle,

which is why nelle is the last part of the directory's name.

Path

Notice that there are two meanings for the

/ character.

When it appears at the front of a file or directory name,

it refers to the root directory. When it appears inside a name,

it's just a separator.Listing the contents of directories and moving around

But how can we tell what's in directories, and how can we move around the file system?

We're currently in our home directory, and can see what's in it by running

ls,

which stands for "listing" (the ... refers to other files and directories that have been left out for clarity):ls

shell-novice Misc Solar.pdf Applications Movies Teaching Desktop Music ThunderbirdTemp Development Notes.txt VirtualBox VMs Documents Pictures bin Downloads Pizza.cfg mbox ...

Of course, this listing will depend on what you have in your own home directory.

If you're using Git Bash on Windows, you'll find that it looks a little different, with characters such as

/ added to some names.

This is because Git Bash automatically tries to highlight the type of thing it is. For example, / indicates that entry is a directory.

There's a way to also highlight this on Mac and Linux machines which we'll see shortly!We need to get into the repository directory

shell-novice, so what if we want to change our current working directory?

Before we do this,

pwd shows us that we're in /Users/nelle.pwd

/Users/nelle

Let's first get hold of some example files we can explore. First, download the example zip file to your home directory.

If on WSL or Linux (e.g. Ubuntu or the Ubuntu VM), then do:

wget https://train.oxrse.uk/material/HPCu/technology_and_tooling/bash_shell/shell-novice.zip

Or, if on a Mac, do:

curl -O https://train.oxrse.uk/material/HPCu/technology_and_tooling/bash_shell/shell-novice.zip

Once done, you can unzip this file using the

unzip command in Bash, which will unpack all the files

in this zip archive into the current directory:unzip shell-novice.zip

If you do

ls now, you should see a new shell-novice directory.We can use

cd followed by a directory name to change our working directory.

cd stands for "change directory",

which is a bit misleading:

the command doesn't change the directory,

it changes the shell's idea of what directory we are in.cd shell-novice

cd doesn't print anything,

but if we run pwd after it, we can see that we are now in /Users/nelle/shell-novice:pwd

/Users/nelle/shell-novice

If we run

ls without arguments now,

it lists the contents of /Users/nelle/shell-novice,

because that's where we now are:ls

AUTHORS Gemfile _config.yml _includes bin files setup.md CITATION LICENSE.md _episodes _layouts code index.md shell CODE_OF_CONDUCT.md Makefile _episodes_rmd aio.md data reference.md slides CONTRIBUTING.md README.md _extras assets fig requirements.txt

ls prints the names of the files and directories in the current directory in alphabetical order,

arranged neatly into columns (where there is space to do so).

We can make its output more comprehensible by using the flag -F,

which tells ls to add a trailing / to the names of directories:ls -F

AUTHORS Gemfile _config.yml _includes/ bin/ files/ setup.md CITATION LICENSE.md _episodes/ _layouts/ code/ index.md shell/ CODE_OF_CONDUCT.md Makefile _episodes_rmd/ aio.md data/ reference.md slides/ CONTRIBUTING.md README.md _extras/ assets/ fig/ requirements.txt

Here,

we can see that this directory contains a number of sub-directories.

The names that don't have trailing slashes,

like

reference.html, setup.md, and requirements.txt,

are plain old files.

And note that there is a space between ls and -F:

without it,

the shell thinks we're trying to run a command called ls-F,

which doesn't exist.What's In A Name?

You may have noticed that all of these files' names are "something dot

something". This is just a convention: we can call a file

mythesis or

almost anything else we want. However, most people use two-part names

most of the time to help them (and their programs) tell different kinds

of files apart. The second part of such a name is called the

filename extension, and indicates

what type of data the file holds: .txt signals a plain text file, .pdf

indicates a PDF document, .html is an HTML file, and so on.This is just a convention, albeit an important one. Files contain

bytes: it's up to us and our programs to interpret those bytes

according to the rules for PDF documents, images, and so on.

Naming a PNG image of a whale as

whale.mp3 doesn't somehow

magically turn it into a recording of whalesong, though it might

cause the operating system to try to open it with a music player

when someone double-clicks it.For this exercise, we need to change our working directory to

shell-novice, and then shell (within the shell-novice directory). As we have already used cd to move into shell-novice we can get to shell by using cd again:cd shell

Note that we are able to add directories together by using

/.

Now if we view the contents of that directory:ls -F

shell-novice-data.zip tools/ test_directory/

Note that under Git Bash in Windows, the

/ is appended automatically.Now let's take a look at what's in the directory

test_directory, by running ls -F test_directory. So here, we're giving the shell the command ls with the arguments -F and test_directory. The first argument is the -F flag we've seen before. The second argument --- the one without a leading dash --- tells ls that

we want a listing of something other than our current working directory:ls -F test_directory

creatures/ molecules/ notes.txt solar.pdf data/ north-pacific-gyre/ pizza.cfg writing/

The output shows us that there are some files and sub-directories.

Organising things hierarchically in this way helps us keep track of our work:

it's a bit like using a filing cabinet to store things. It's possible to put hundreds of files in our home directory, for example,

just as it's possible to pile hundreds of printed papers on our desk,

but it's a self-defeating strategy.

Notice, by the way, that we spelled the directory name

test_directory, and it doesn't have a trailing slash.

That's added to directory names by ls when we use the -F flag to help us tell things apart.

And it doesn't begin with a slash because it's a relative path -

it tells ls how to find something from where we are,

rather than from the root of the file system.Parameters vs. Arguments

According to Wikipedia,

the terms argument and parameter

mean slightly different things.

In practice,

however,

most people use them interchangeably or inconsistently,

so we will too.

If we run

ls -F /test_directory (with a leading slash) we get a different response,

because /test_directory is an absolute path:ls -F /test_directory

ls: /test_directory: No such file or directory

The leading

/ tells the computer to follow the path from the root of the file system,

so it always refers to exactly one directory,

no matter where we are when we run the command.

In this case, there is no data directory in the root of the file system.Typing

ls -F test_directory is a bit painful, so a handy shortcut is to type in the first few letters and press the TAB key, for example:ls -F tes

Pressing TAB, the shell automatically completes the directory name:

ls -F test_directory/

This is known as tab completion on any matches with those first few letters.

If there are more than one files or directories that match those letters, the shell will show you both --- you can then enter more characters (then using TAB again) until it is able to identify the precise file you want and finish the tab completion.

Let's change our directory to

test_directory:cd test_directory

We know how to go down the directory tree:

but how do we go up?

We could use an absolute path, e.g.

cd /Users/nelle/shell-novice/novice/shell.but it's almost always simpler to use

cd .. to go up one level:pwd

/Users/nelle/shell-novice/novice/shell/test_directory

cd ..

.. is a special directory name meaning

"the directory containing this one",

or more succinctly,

the parent of the current directory.pwd

/Users/nelle/shell-novice/novice/shell/

Let's go back into our test directory:

cd test_directory

The special directory

.. doesn't usually show up when we run ls.

If we want to display it, we can give ls the -a flag:ls -F -a

./ creatures/ molecules/ notes.txt solar.pdf ../ data/ north-pacific-gyre/ pizza.cfg writing/

-a stands for "show all";

it forces ls to show us file and directory names that begin with .,

such as .. (which, if we're in /Users/nelle/shell-novice/novice/shell/test_directory, refers to the /Users/nelle/shell-novice/novice/shell directory).

As you can see,

it also displays another special directory that's just called .,

which means "the current working directory".

It may seem redundant to have a name for it,

but we'll see some uses for it soon.Special Names

The special names

. and .. don't belong to ls;

they are interpreted the same way by every program.

For example,

if we are in /Users/nelle/shell-novice,

the command ls .. will give us a listing of /Users/nelle,

and the command cd .. will take us back to /Users/nelle as well.How

., .. and ~ behave is a feature of how Bash represents

your computer's file system, not any particular program you can run in it.Another handy feature is that we can reference our home directory with

~, e.g.:ls ~/shell-novice

AUTHORS Gemfile _config.yml _includes bin files setup.md CITATION LICENSE.md _episodes _layouts code index.md shell CODE_OF_CONDUCT.md Makefile _episodes_rmd aio.md data reference.md slides CONTRIBUTING.md README.md _extras assets fig requirements.txt

Which again shows us our repository directory.

Note that

~ only works if it is the first character in the

path: here/there/~/elsewhere is not /Users/nelle/elsewhere.Exercises

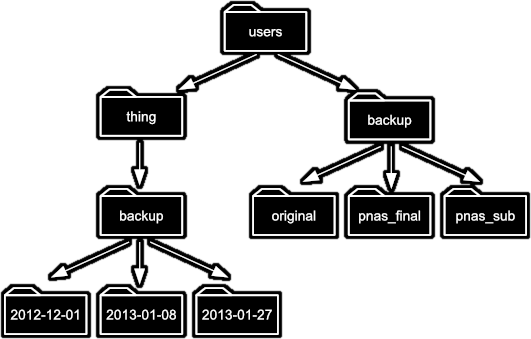

Relative Path Resolution

If

pwd displays /Users/thing, what will ls ../backup display?../backup: No such file or directory2012-12-01 2013-01-08 2013-01-272012-12-01/ 2013-01-08/ 2013-01-27/original pnas_final pnas_sub

ls Reading Comprehension

If

pwd displays /Users/backup,

and -r tells ls to display things in reverse order,

what command will display:`pnas-sub/ pnas-final/ original/`

ls pwdls -r -Fls -r -F /Users/backup- Either #2 or #3 above, but not #1.