Non-blocking Communication

In the previous episodes, we learnt how to send messages between two ranks or collectively to multiple ranks. In both cases, we used blocking communication functions which meant our program wouldn’t progress until the communication had completed. It takes time and computing power to transfer data into buffers, to send that data around (over the network) and to receive the data into another rank. But for the most part, the CPU isn’t actually doing much at all during communication, when it could still be number crunching.

Why bother with non-blocking communication?

Non-blocking communication is communication which happens in the background. So we don’t have to let any CPU cycles go to waste! If MPI is dealing with the data transfer in the background, we can continue to use the CPU in the foreground and keep doing tasks whilst the communication completes. By overlapping computation with communication, we hide the latency/overhead of communication. This is critical for lots of HPC applications, especially when using lots of CPUs, because, as the number of CPUs increases, the overhead of communicating with them all also increases. If you use blocking synchronous sends, the time spent communicating data may become longer than the time spent creating data to send! All non-blocking communications are asynchronous, even when using synchronous sends, because the communication happens in the background, even though the communication cannot complete until the data is received.

So, how do I use non-blocking communication?

Just as with buffered, synchronous, ready and standard sends, MPI has to be programmed to use either blocking or non-blocking communication. For almost every blocking function, there is a non-blocking equivalent. They have the same name as their blocking counterpart, but prefixed with "I". The "I" stands for "immediate", indicating that the function returns immediately and does not block the program. The table below shows some examples of blocking functions and their non-blocking counterparts.

| Blocking | Non-blocking |

|---|---|

MPI_Bsend() | MPI_Ibsend() |

MPI_Barrier() | MPI_Ibarrier() |

MPI_Reduce() | MPI_Ireduce() |

But, this isn't the complete picture. As we'll see later, we need to do some additional bookkeeping to be able to use

non-blocking communications.

By effectively utilising non-blocking communication, we can develop applications that scale significantly better during intensive communication. However, this comes with the trade-off of both increased conceptual and code complexity.

Since non-blocking communication doesn't keep control until the communication finishes, we don't actually know if a communication has finished unless we check; this is usually referred to as synchronisation, as we have to keep ranks in sync to ensure they have the correct data. So whilst our program continues to do other work, it also has to keep pinging to see if the communication has finished,

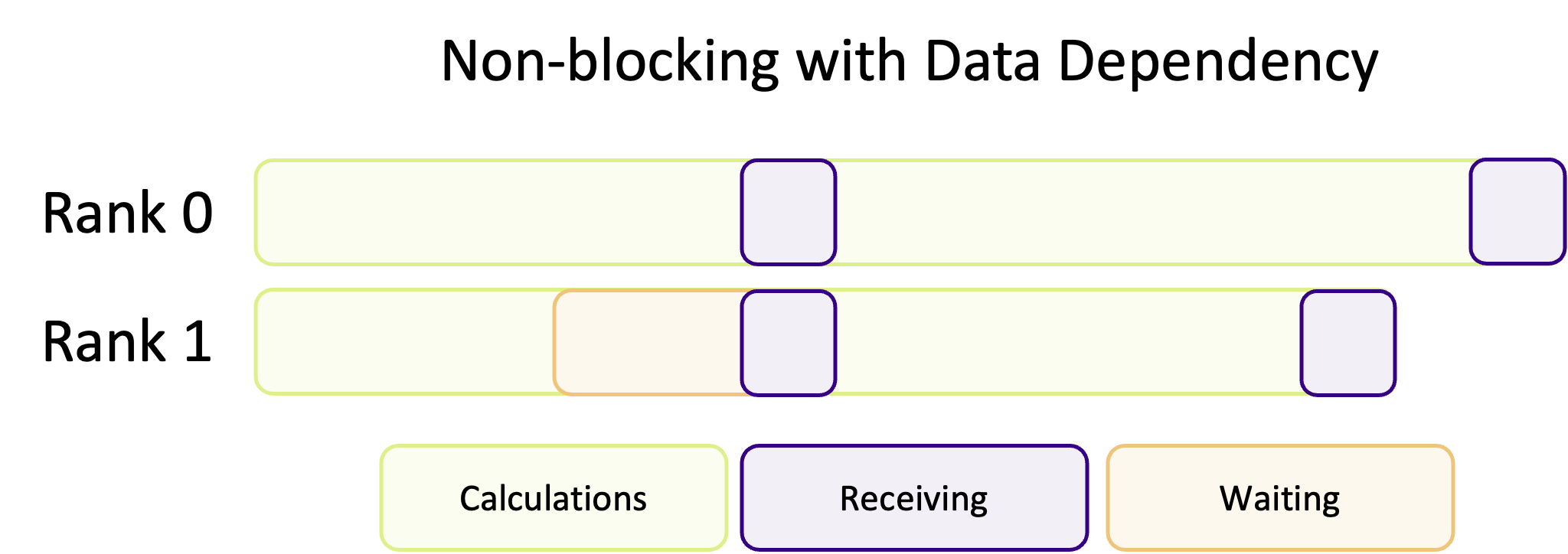

to ensure ranks are synchronised. If we check too often, or don't have enough tasks to "fill in the gaps", then there is no advantage to using non-blocking communication, and we may replace communication overheads with time spent keeping ranks in sync! It is not always clear-cut or predictable if non-blocking communication will improve performance. For example, if one ranks depends on the data of another, and there are no tasks for it to do whilst it waits, that rank will wait around until the data is ready, as illustrated in the diagram below. This essentially makes that non-blocking communication a blocking communication.

Therefore, unless our code is structured to take advantage of being able to overlap communication with computation, non-blocking communication adds complexity to our code for no gain.

Advantages and Disadvantages

What are the main advantages of using non-blocking communication, compared to blocking? What about any disadvantages?

Point-to-point communication

For each blocking communication function we've seen, a non-blocking variant exists.

For example, if we take

MPI_Send(), the non-blocking variant is MPI_Isend() which has the arguments:int MPI_Isend( void *buf, int count, MPI_Datatype datatype, int dest, int tag, MPI_Comm comm, MPI_Request *request );

*buf: | The data to be sent |

count: | The number of elements of data |

datatype: | The data types of the data |

dest: | The rank to send data to |

tag: | The communication tag |

comm: | The communicator |

*request: | The request handle, used to track the communication |

The arguments are identical to

MPI_Send(), other than the addition of the *request argument.

This argument is known as a handle (because it "handles" a communication request) which is used to track the progress of a (non-blocking) communication.When we use non-blocking communication, we have to follow it up with

MPI_Wait() to synchronise

the program and make sure *buf is ready to be re-used. This is incredibly important to do.

Suppose we are sending an array of integers,MPI_Isend(some_ints, 5, MPI_INT, 1, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD, &request); some_ints[1] = 5; /* !!! don't do this !!! */

Modifying

some_ints before the send has completed is undefined behaviour, and can result in breaking results! For

example, if MPI_Isend() decides to use its buffered mode then modifying some_ints before it's finished being copied to

the send buffer means the wrong data is sent. Every non-blocking communication has to have a corresponding MPI_Wait(), to wait and synchronise the program to ensure that the data being sent is ready to be modified again. MPI_Wait() is a blocking function which will only return when a communication has finished.int MPI_Wait( MPI_Request *request, MPI_Status *status );

*request: | The request handle for the communication |

*status: | The status handle for the communication |

Once we have used

MPI_Wait() and the communication has finished, we can safely modify some_ints again. To receive

the data send using a non-blocking send, we can use either the blocking MPI_Recv() or it's non-blocking variant.int MPI_Irecv( void *buf, int count, MPI_Datatype datatype, int source, int tag, MPI_Comm comm, MPI_Request *request, );

*buf: | A buffer to receive data into |

count: | The number of elements of data to receive |

datatype: | The data type of the data |

source: | The rank to receive data from |

tag: | The communication tag |

comm: | The communicator |

*request: | The request handle for the receive |

True or False?

Is the following statement true or false? Non-blocking communication guarantees immediate completion of data transfer.

In the example below, an array of integers (

some_ints) is sent from rank 0 to rank 1 using non-blocking communication.MPI_Status status; MPI_Request request; int recv_ints[5]; int some_ints[5] = { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 }; if (my_rank == 0) { MPI_Isend(some_ints, 5, MPI_INT, 1, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD, &request); MPI_Wait(&request, &status); some_ints[1] = 42; // After MPI_Wait(), some_ints has been sent and can be modified again } else { MPI_Irecv(recv_ints, 5, MPI_INT, 0, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD, &request); MPI_Wait(&request, &status); int data_i_wanted = recv_ints[2]; // recv_ints isn't guaranteed to have the correct data until after MPI_Wait() }

The code above is functionally identical to blocking communication, because of

MPI_Wait() is blocking. The program will not continue until MPI_Wait() returns. Since there is no additional work between the communication call and blocking wait, this is a poor example of how non-blocking communication should be used. It doesn't take advantage of the asynchronous nature of non-blocking communication at all. To really make use of non-blocking communication, we need to interleave computation (or any busy work we need to do) with communication, such as in the next example.MPI_Status status; MPI_Request request; if (my_rank == 0) { /* This send important_data without being blocked and move into the next work */ MPI_Isend(important_data, 16, MPI_INT, 1, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD, &request); } else { /* Start listening for the message from the other rank, but isn't blocked */ MPI_Irecv(important_data, 16, MPI_INT, 0, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD, &request); } /* Whilst the message is still sending or received, we should do some other work to keep using the CPU (which isn't required for most of the communication. IMPORTANT: the work here cannot modify or rely on important_data */ clear_model_parameters(); initialise_model(); /* Once we've done the work which doesn't require important_data, we need to wait until the data is sent/received if it hasn't already */ MPI_Wait(&request, &status); /* Now the model is ready and important_data has been sent/received, the simulation carries on */ simulate_something(important_data);

What About Deadlocks?

Deadlocks are easily created when using blocking communication.

The code snippet below shows an example of deadlock from one of the previous episodes.

if (my_rank == 0) { MPI_Send(&numbers, 8, MPI_INT, 1, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD); MPI_Recv(&numbers, 8, MPI_INT, 1, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD, &status); } else { MPI_Send(&numbers, 8, MPI_INT, 0, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD); MPI_Recv(&numbers, 8, MPI_INT, 0, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD, &status); }

If we changed to non-blocking communication, do you think there would still be a deadlock? Try writing your own non-blocking version.

To wait, or not to wait

In some sense, by using

MPI_Wait() we aren't fully non-blocking because we still block execution whilst we wait for communications to complete. To be "truly" asynchronous we can use another function called MPI_Test() which, at face value, is the non-blocking counterpart of MPI_Wait(). When we use MPI_Test(), it checks if a communication is finished and sets the value of a flag to true if it is and returns. If a communication hasn't finished, MPI_Test() still returns but the value of the flag is false instead. MPI_Test() has the following arguments:int MPI_Test( MPI_Request *request, int *flag, MPI_Status *status, );

*request: | The request handle for the communication |

*flag: | A flag to indicate if the communication has completed |

*status: | The status handle for the communication |

*request and *status are the same you'd use for MPI_Wait(). *flag is the variable which is modified to indicate if the communication has finished or not. Since it's an integer, if the communication hasn't finished then flag == 0.We use

MPI_Test() is much the same way as we'd use MPI_Wait(). We start a non-blocking communication, and keep doing other, independent, tasks whilst the communication finishes. The key difference is that since MPI_Test() returns immediately, we may need to make multiple calls before the communication is finished. In the code example below, MPI_Test() is used within a while loop which keeps going until either the communication has finished or until there is no other work left to do.MPI_Status status; MPI_Request request; MPI_Irecv(recv_buffer, 16, MPI_INT, 0, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD, &request); // We need to define a flag, to track when the communication has completed int comm_completed = 0; // One example use case is keep checking if the communication has finished, and continuing // to do CPU work until it has while (!comm_completed && work_still_to_do()) { do_some_other_work(); // MPI_Test will return flag == true when the communication has finished MPI_Test(&request, &comm_completed, &status); } // If there is no more work and the communication hasn't finished yet, then we should wait // for it to finish if (!comm_completed) { MPI_Wait(&request, &status); }

Dynamic task scheduling

Dynamic task schedulers are a class of algorithms designed to optimise the work load across ranks.

The most efficient, and, really, only practical, implementations use non-blocking communication to periodically check the work balance and asynchronously assign and send additional work to a rank, in the background, as it continues to work on its current queue of work.

An interesting aside: communication timeouts

Non-blocking communication gives us a lot of flexibility, letting us write complex communication algorithms to experiment and find the right solution. One example of that flexibility is using

MPI_Test() to create a communication timeout algorithm.#define COMM_TIMEOUT 60 // seconds clock_t start_time = clock(); double elapsed_time = 0.0; int comm_completed = 0 while (!comm_completed && elapsed_time < COMM_TIMEOUT) { // Check if communication completed MPI_Test(&request, &comm_completed, &status); // Update elapsed time elapsed_time = (double)(clock() - start_time) / CLOCKS_PER_SEC; } if (elapsed_time >= COMM_TIMEOUT) { MPI_Cancel(&request); // Cancel the request to stop the, e.g. receive operation handle_communication_errors(); // Put the program into a predictable state }

Something like this would effectively remove deadlocks in our program, and allows us to take appropriate actions to recover the program back into a predictable state.

In reality, however, it would be hard to find a useful and appropriate use case for this in scientific computing.

In any case, though, it demonstrates the power and flexibility offered by non-blocking communication.

Try it yourself

In the MPI program below, a chain of ranks has been set up so one rank will receive a message from the rank to its left and send a message to the one on its right, as shown in the diagram below:

For following skeleton below, use non-blocking communication to send

send_message to the right and receive a message from the left rank. Create two programs, one using MPI_Wait() and the other using MPI_Test().#include <mpi.h> #include <stdio.h> #define MESSAGE_SIZE 32 int main(int argc, char **argv) { int my_rank; int num_ranks; MPI_Init(&argc, &argv); MPI_Comm_rank(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &my_rank); MPI_Comm_size(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &num_ranks); if (num_ranks < 2) { printf("This example requires at least two ranks\n"); return MPI_Finalize(); } char send_message[MESSAGE_SIZE]; char recv_message[MESSAGE_SIZE]; int right_rank = (my_rank + 1) % num_ranks; int left_rank = my_rank < 1 ? num_ranks - 1 : my_rank - 1; sprintf(send_message, "Hello from rank %d!", my_rank); // Your code goes here return MPI_Finalize(); }

The output from your program should look something like this:

Rank 0: message received -- Hello from rank 3! Rank 1: message received -- Hello from rank 0! Rank 2: message received -- Hello from rank 1! Rank 3: message received -- Hello from rank 2!

Collective communication

Since the release of MPI 3.0, the collective operations have non-blocking versions.

Using these non-blocking collective operations is as easy as we've seen for point-to-point communication in the last section.

If we want to do a non-blocking reduction, we'd use

MPI_Ireduce():int MPI_Ireduce( const void *sendbuf, void *recvbuf, int count, MPI_Datatype datatype, MPI_Op op, int root, MPI_Comm comm, MPI_Request *request, );

*sendbuf: | The data to be reduced by the root rank |

*recvbuf: | A buffer to contain the reduction output |

count: | The number of elements of data to be reduced |

datatype: | The data type of the data |

op: | The reduction operation to perform |

root: | The root rank, which will perform the reduction |

comm: | The communicator |

*request: | The request handle for the communicator |

As with

MPI_Send() vs. MPI_Isend() the only change in using the non-blocking variant of MPI_Reduce() is the addition of the *request argument, which returns a request handle.

This is the request handle we'll use with either MPI_Wait() or MPI_Test() to ensure that the communication has finished, and been successful.

The below code examples shows a non-blocking reduction:MPI_Status status; MPI_Request request; int recv_data; int send_data = my_rank + 1; /* MPI_Iallreduce is the non-blocking version of MPI_Allreduce. This reduction operation will sum send_data for all ranks and distribute the result back to all ranks into recv_data */ MPI_Iallreduce(&send_data, &recv_data, 1, MPI_INT, MPI_SUM, MPI_COMM_WORLD, &request); /* Remember, using MPI_Wait() straight after the communication is equivalent to using a blocking communication */ MPI_Wait(&request, &status);

What's `MPI_Ibarrier()` all about?

In the previous episode, we learnt that

MPI_Barrier() is a collective operation we can use to bring all the ranks back into synchronisation with one another.

How do you think the non-blocking variant, MPI_Ibarrier(), is used and how might you use this in your program?

You may want to read the relevant documentation first.Reduce and Broadcast

Using non-blocking collective communication, calculate the sum of

my_num = my_rank + 1 from each MPI rank and broadcast the value of the sum to every rank.

To calculate the sum, use either MPI_Igather() or MPI_Ireduce().

You should use the code below as your starting point.#include <mpi.h> #include <stdio.h> int main(int argc, char **argv) { int my_rank; int num_ranks; MPI_Init(&argc, &argv); MPI_Comm_rank(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &my_rank); MPI_Comm_size(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &num_ranks); if (num_ranks < 2) { printf("This example needs at least 2 ranks\n"); MPI_Finalize(); return 1; } int sum = 0; int my_num = my_rank + 1; printf("Start : Rank %d: my_num = %d sum = %d\n", my_rank, my_num, sum); // Your code goes here printf("End : Rank %d: my_num = %d sum = %d\n", my_rank, my_num, sum); return MPI_Finalize(); }

For two ranks, the output should be:

Start : Rank 0: my_num = 1 sum = 0 Start : Rank 1: my_num = 2 sum = 0 End : Rank 0: my_num = 1 sum = 3 End : Rank 1: my_num = 2 sum = 3